Taking it to the Streets

by Cynthia Berger

Before the upstate New York winter brought an icy crisp coating to the surface of Oneida Lake, Katie Arnold '04 spent a lot of her time meandering across its blue waters in a powerboat. But the Hamilton senior wasn't sunbathing, water skiing or even pursuing the lake's famous walleyes. Instead, she was collecting data for her senior thesis. A geology major, Arnold is investigating why sediments have started to pile up at the mouth of Oneida Creek, a tributary to the lake.

Her results are of more than academic interest, because here in the central New York region, Oneida Lake's sport fishery is a major economic resource. By clouding the water and coating the lake bottom, the excess sediment could change the lake's ecological balance and harm the fishery. The mounds of sand and silt accumulating just below the water's surface already interfere with recreational boating.

fter Arnold collects her sediment samples, analyzes them in the lab and presents her thesis to her advisor, Eugene Domack, her work will become part of a larger study of lake sedimentation that the geology professor is conducting with funding from the Central New York Regional Planning Board. "The board will use this and other research to work up a watershed development plan," Domack explains. "The plan will help local governments evaluate any future development that may affect the quality of the lake. It will also help them weigh the options for remediation of adverse environmental impacts."

A muddy Katie Arnold '04 collecting samples.

Arnold is not the only Hamilton senior doing research with tangible public policy implications. Many students make similar choices -- in part because of an up-front institutional outlook that encourages them to climb down from the ivory tower and grapple with real-world, science-based issues.

Hamilton's Arthur Levitt Public Affairs Center -- where "The Environment" is the topic for this year's speakers series -- is a good example of this outlook; director and economics professor Paul Hagstrom says that the center identifies local public policy issues that would benefit from further research, then recruits Hamilton students to carry out the investigations. "Right now, for example, we've got one group of students conducting a study requested by a group of Utica-based doctors on the factors associated with increased risk of stroke," he says.

Meanwhile, back in the classroom, science professors make a point of connecting abstract ideas with concrete problems. Domack routinely takes his sedimentology and paleoclimate classes on field trips to Oneida Lake. "We'll talk about, 'Why is it important to learn how a river erodes and transports sediments?' or 'Why do we study the action of waves on beach sand?'" he says. "The answer is not simply that these are interesting processes; we also study them because they impact our local community, and they will impact the communities where students will live in the future.

"Students have the choice to get involved with all kinds of public policy problems," he adds. "They can make such great contributions, and they should motivate themselves to do that."

Like Katie Arnold, Bill Haley '04 has taken this kind of advice to heart. Although not a science concentrator, the public policy major is investigating the quality and efficiency of emergency response crews in New York's Westchester County where he grew up and where his family still lives. A member of the Clinton Fire Department and a certified EMT, Haley got the idea for his senior thesis last summer when he interned with Westchester's Department of Emergency Services. His duties included daily information updates to the computer-aided dispatch system and work on evacuation planning with Westchester's Office of Emergency Management.

Billy Haley '04 ready for duty as an EMT at the Clinton Fire Department.

The concern in Westchester County, says Haley, is a lack of uniform emergency service. The region is a mix of rural and densely populated areas, served by both publicly and privately owned ambulance companies. By gathering statistics on ambulance response times and by studying the distribution of basic versus advanced life support units, Haley hopes to come up with recommendations that could help ensure optimal emergency care throughout the region.

While Haley is acting locally for his senior thesis, Lindsey Martin '04 is thinking globally for hers. The world politics major, who is also pre-med and a Schambach Scholar, plans to investigate whether AIDS/HIV clinics in Africa actually benefit from international foreign aid programs as much as these programs' creators intend.

Lindsay Martin '04 traveled to Barcelona, Spain, in the summer of 2002 to volunteer at the International AIDS Conference. She attended rallies (above) and learned more about the magnitude and impact of the disease, including taking a tour of a vehicle used by health workers to test and treat patients in rural areas (below).

Martin became interested in the biology and pathology of AIDS while taking pre-med classes during an unconventional junior year abroad at Canada's McGill University. She volunteered at a Montreal-based AIDS community resource center, where she saw firsthand the particular challenges AIDS patients face. This spring, thanks to an Emerson Scholarship designed to support faculty/student research collaborations, Martin will volunteer at an AIDS/HIV clinic in South Africa. Meanwhile, she already used her Schambach support to bring well-known Chinese AIDS activist Dr. Wan Yan Hai to campus for a guest lecture last spring. She also traveled to Barcelona, Spain, in the summer of 2002 to attend the U.N.'s 14th International AIDS Conference.

"It's incredibly difficult to go into a situation where there is sadness and disease. You don't know what you're going to see, but you know it isn't going to be good," says Martin, who plans to pursue an M.S. in public health before going to medical school to specialize in epidemiology or tropical disease. "There's such a need out there. To me, this is more than a career path -- it's a calling. I'm passionate about it."

Jess Woodward '04 is addressing the AIDS epidemic on the home front for her senior thesis. She is investigating the link between the quality of health insurance and quality of life for AIDS patients in America. Woodward got the idea for her research during a summer internship with Food and Friends, a Washington, D.C., nonprofit that provides such services as nutritionally appropriate meals to patients with HIV and AIDS.

"The internship was a good 'real-life' experience -- working nine-to-five, riding on the Metro," Woodward notes. At the same time, as she delivered meals or dropped in for "buddy visits," Woodward made some alarming observations about her clients' lives. "So many people weren't getting to the pharmacy for their medicine just because insurance didn't cover a bus ride," she says. Other Medicaid patients endured long waiting lists to enroll in drug trials; all too often, the cutting-edge new medicines came too late. "That's really when I decided to start my research," she says.

Speaking of real-life experiences, if you'd like to see how Chris LaRosa's latest research project is coming along, check the digital snapshots at http://watson.chrislarosa.net. A member of the Class of '03, LaRosa is spending his postgrad year circling the globe on a Thomas J. Watson Fellowship to study countries that, in his words, "have set themselves apart from their peers by rapidly adopting new communication technologies." He's especially interested in how Internet technology is changing the way citizens get their news and participate in democratic processes.

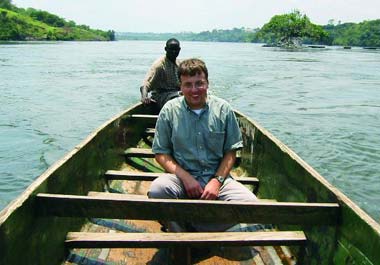

Watson Fellow Chris LaRosa '03 floats along the head of the river Nile in Jinja, Uganda.

The computer science major and former Spectator editor credits a public affairs journalism class at Hamilton with fanning his interest in the role of the press in society. For his senior thesis, he studied how to make handheld computers -- now mostly used as electronic datebooks -- more powerful and useful. His year-long itinerary as a Watson Fellow includes stops in such nations as Tanzania, which has opened the world's first telecommunications center for refugees; Mexico, which is creating free Internet access centers for rural users; and Slovenia, where, in recent elections, citizens used cellular text messaging to get out the vote.

It's a common theme among Hamilton's faculty that a strong science background and engagement in policy issues prepares students to be responsible citizens. For her summer research project, Emerson Scholar Joan Booth '04 took a look at how well other colleges do in this vein. With biology professor Jinnie Garrett, the psychology major investigated the extent to which ethical issues are included in introductory-level college genetics classes -- an important question given that genetics generates some of society's thorniest medical ethics issues, like cloning and stem-cell research.

Joan Booth '04 tallying the results of her survey on the emphasis of ethics in introductory genetics classes.

Booth and Garrett mailed surveys to genetics instructors at 500 liberal arts colleges and universities; summarizing the results, Booth reports: "There seems to be a disconnect between what people think should be happening in genetics classrooms and what actually is happening." A mere four percent of the schools responding to the survey required biology majors to take a course on ethics in science, while the typical genetics instructor spent less than five percent of class time addressing ethical and social issues. More than a third of the schools responding to the survey don't offer even a single course on ethics in science.

Garrett notes that Hamilton stands out as a data point in the survey. Here, the study of ethical issues is an express part of the science curriculum. For example, all senior biology majors take a mini-course on research ethics, so that, as they design and carry out their own research, they understand the difference between honest errors, negligent errors and outright misconduct. Meanwhile, in 2002, at Garrett's urging, the department also adopted a policy requiring biology majors to take a course that addresses issues of public policy or ethics from the perspective of science and technology. Environmental Studies 150 (Society and the Environment) and Philosophy 271 (Ethics of Professions and Practices) are examples of classes that fulfill the requirement. "As you can see from the survey results, this kind of requirement is quite unusual," Garrett notes.

Faculty members consciously make ethical issues a routine part of course content at Hamilton.Garrett's introductory biology class, for example, holds a series of debates on the use of genetically modified organisms in agriculture. Over in the chemistry department, says associate dean of the faculty and chemistry professor Timothy Elgren, students might look at the local use of pesticides on food crops and debate the scientific evidence about human health risks. "It contextualizes the science in a way that motivates interest in learning," he says. "I think this is some of the most exciting teaching that we do."

It can be all too easy for students to overlook ethical and moral concerns when they're consumed with "getting up to speed" on a research project, Elgren notes. "By incorporating these issues into laboratory and course work early in their careers, we can emphasize how the ethical conduct of scientists plays a central role in the integrity of their work -- and in generating public trust in the results."

This spring Elgren will be team-teaching (with biology professor Herman Lehman) a sophomore seminar that fulfills the biology ethics requirement. It's called Scientific and Social Perspectives on HIV and AIDS. "We're focusing on what is currently known about the disease and its devastating impact," he notes, "but also how public understanding of AIDS has evolved as scientists learn more about the disease itself."

If Hamilton prepares students to be engaged in their communities post-graduation, it's worth noting that many Hamilton students who have chosen to focus on public policy issues in their thesis research already have a long history of volunteer involvement. Haley finds deep satisfaction in his work as a Clinton firefighter. "It's nice to have this connection -- to walk around downtown and say hello to friends who aren't affiliated with the College," he says. "I've gotten to know a lot of people in Clinton whom I never would have met."

Woodward volunteers in Utica with an afterschool program for kids who would otherwise go home to an empty house. "Satisfied isn't a strong enough word to explain how I feel about my experience at Hamilton," she reflects. "You don't come here just to study. I can't think of too many people I know who aren't involved in some kind of community service or volunteer program." At latest count more than 400 of Hamilton's students volunteer with the Hamilton Action Volunteer Outreach Coalition (HAVOC) each year.

Meanwhile, though she feels inspired by her experience at the AIDS conference in Barcelona, Martin has one regret: a McGill classmate who was to travel with her and share in presenting a paper ultimately stayed behind because the Canadian university couldn't fund his travel. "I will never take for granted how generous Hamilton is in giving students opportunities to do things," she says.

Though many of the students mentioned here have plans for graduate study -- Martin is thinking about medical school; Woodward is looking at graduate studies in the social sciences -- Domack reflects that a strong science background prepares Hamilton students for more than just advanced study. "Whatever their career path, they are scientifically educated to make decisions in their own communities," he says. Elgren agrees. "To passively defer decisions on science issues to the scientists means disengaging from democracy in some of the most important debates that we face as a society," he says, citing as examples genetically modified foods, reproductive rights, pollution control and land use decisions. "Democracy requires engagement."

Cynthia Berger has worked as a lab instructor for large-enrollment first-year biology classes. She is currently a science writer living in central Pennsylvania.