Necrology

Because Hamilton Remembers

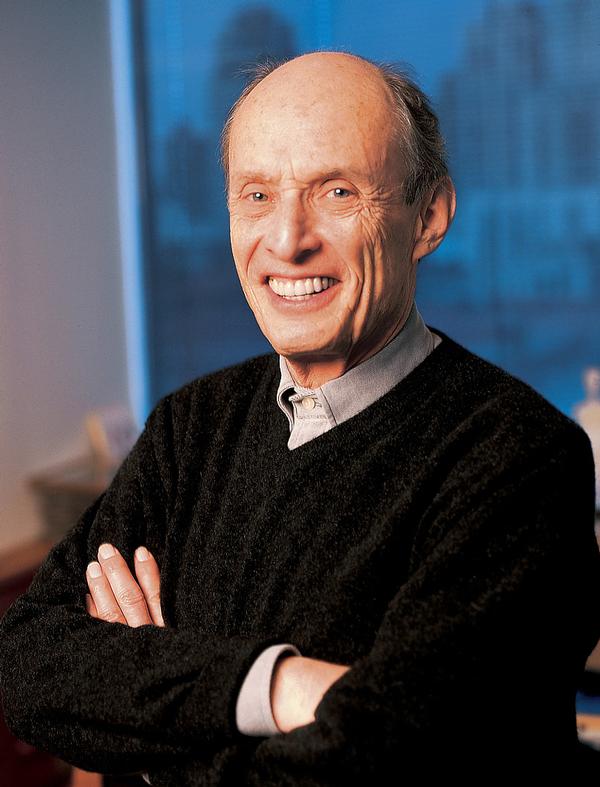

Paul Greengard '48

Dec. 11, 1925-Apr. 13, 2019

Paul Greengard ’48, a Nobel Prize-winning neurobiologist of New York City whose research on how brain cells communicate contributed to advances in treating a wide range of psychological diseases, was born in New York, N.Y., on Dec. 11, 1925. His father was Benjamin Greengard, Class of 1914, a vaudeville performer who became a perfume salesman. His biological mother, the former Pearl Meister, died in childbirth, and he was raised by his stepmother, the former Muriel Richmond.

Greengard attended public schools in Brooklyn and Queens, graduating from Forest Hills High School. In 1943, he enlisted in the Navy and was dispatched to electronic technician school before an assignment at Massachusetts Institute of Technology where, at the age of 17, he helped develop an early-warning radar system to prevent Japanese kamikaze airplanes from destroying American ships in the Pacific.

After three years of active duty, he came to Hamilton in 1946, thanks to the G.I. bill, where he focused his studies in physics and mathematics and, like many students who were veterans, completed his degree requirements in an accelerated fashion. A member of Tau Kappa Epsilon fraternity, he graduated with Phi Beta Kappa honors.

Greengard considered pursuing graduate study in theoretical physics but was concerned about devoting his career to research that might contribute to the development of nuclear weapons. Instead, he entered the field of biophysics, which uses math and physics to solve biological problems.

In 1953, Greengard received his doctorate from Johns Hopkins University. After five years of postdoctoral work and a stint in the pharmaceutical industry, he joined the Yale University faculty in 1968. He moved to New York’s Rockefeller University in 1983. Having established the Laboratory of Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience, he remained an active researcher there until his death, serving as the Vincent Astor Professor and founding director of the Fisher Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research.

According to an obituary prepared by Rockefeller University, when Greengard began his career in the 1950s, scientists believed that nerve transmission was purely electrical, with nerve cells communicating exclusively through neurotransmitters that triggered electrical impulses in their neighbors. Bucking convention, he instead decided to investigate the biochemistry underlying neuronal communication. Over the course of 15 years, Greengard demonstrated that this alternate signaling method, now known as slow synaptic transmission, is in fact the predominant means by which neurons communicate with one another.

“There was virtually no one studying the biochemical basis of how nerve cells function,” Greengard said of his early career in a 2001 interview for the Hamilton Alumni Review. “It was a very interesting period of my life because very, very few people believed I was right and so that was the bad news. It’s very frustrating to hear people say, ‘Oh, that’s nonsense.’ The good news was that I had basically no competition in my field for 15 years and I virtually worked alone. And gradually people began to believe in the validity in it, and now it’s one of the most active areas of all brain research.”

Greengard’s research described how cells react to dopamine, a key chemical messenger in the brain. His work provided the underlying science for many antipsychotic drugs, which modulate the strength of the brain’s chemical signals. For example, he discovered that chemical groups called phosphates within cells trigger a cascade of chemical changes that amplify the dopamine signal. This response, in turn, makes it possible for cells to fire electrical signals. Today the field he pioneered, known as signal transduction, is an important area of study.

In 2000, Greengard’s work earned him the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, an honor he shared with Arvid Carlsson of Sweden and Eric Kandel of the United States for independent discoveries related to the ways brain cells relay messages about movement, memory, and mental states. Their discoveries offered new insights into disorders linked to errors in cell communication, such as Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and drug addiction. He used his $400,000 Nobel award to establish the Pearl Meister Greengard Prize for women in biomedical research, in honor of his mother.

Paul Greengard, who received an honorary degree of Doctor of Science from Hamilton in 2001, died on April 13, 2019, at the age of 93. Survivors include his wife, Ursula von Rydingsvard, three children, and six grandchildren. His uncle was Julius Greengard, Class of 1908.

Note: Memorial biographies published prior to 2004 will not appear on this list.

Necrology Writer and Contact:

Christopher Wilkinson '68

Email: Chris.Wilkinson@mail.wvu.edu

The Joel Bristol Associates

Hamilton has a long-standing history of benefiting from estate and life payment gifts. Thoughtful alumni, parents, and friends who remember Hamilton in their estate plans, including retirement plan beneficiary designations, or complete planned gifts are recognized and honored as Joel Bristol Associates.

Contact

Office / Department Name

Alumni & Parent Relations

Contact Name

Jacke Jones

Director, Alumni & Parent Relations